My previous post was about a testing utility I put together that, given programs written in C that are considered to make use of constructs that are unspecified. For a list of some of these you can check out this page.

Unspecified behaviours

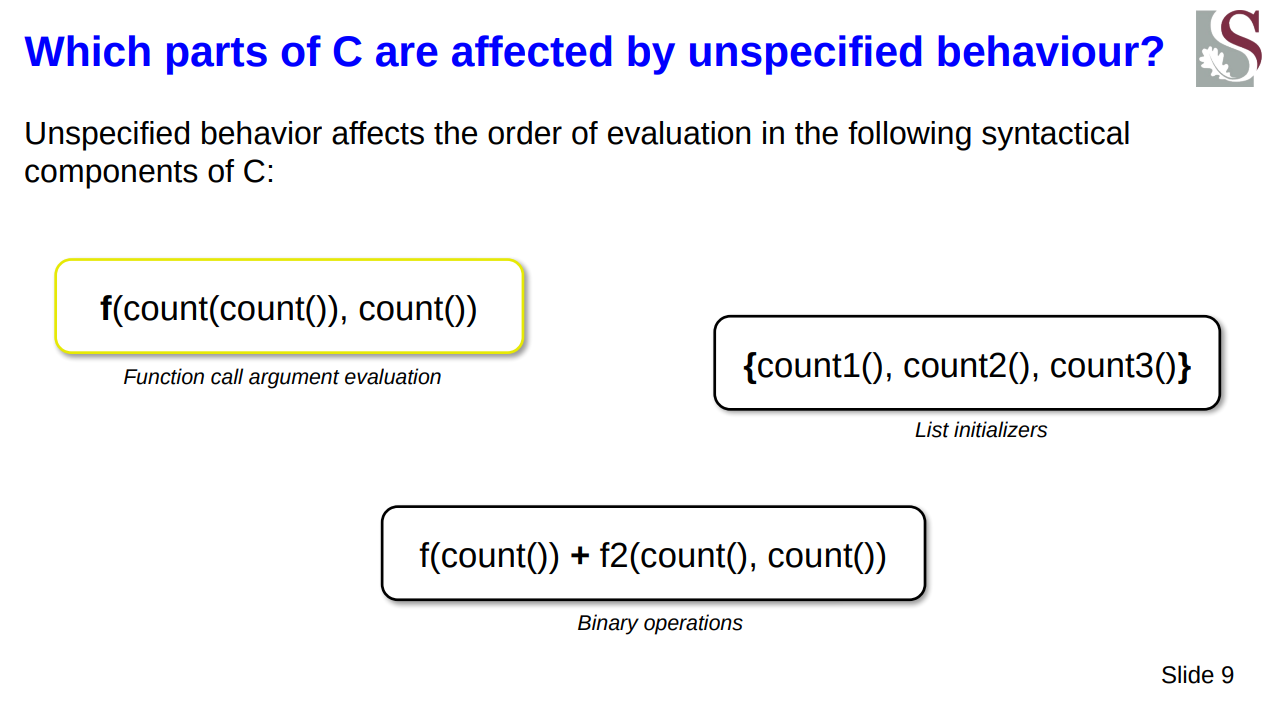

The behaviours which were tested are the following:

- List initializers

- Function call arguments

- Binary operations

These are all said to fall into the unspecified behaviour category, as in there is no specification that says in which order their components should be evaluated (executed).

Testing mechanism

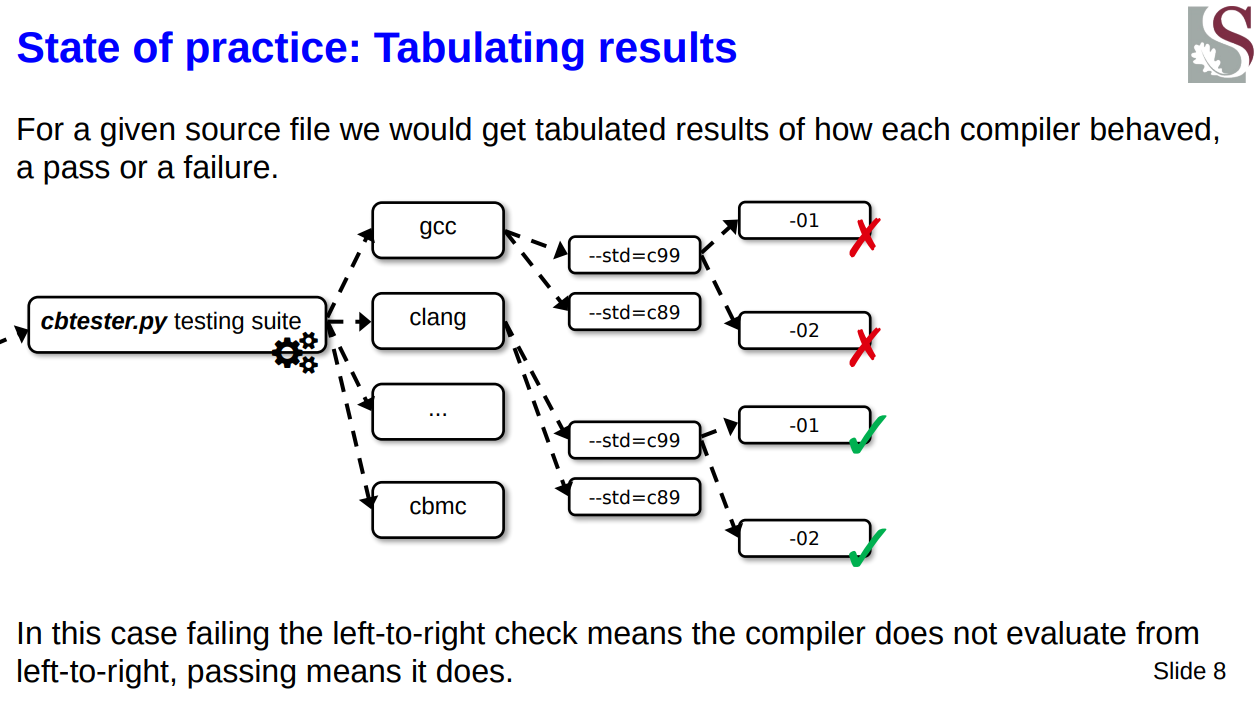

Now, I tested various compilers, then per each of these, various standard flags, per each of those various optimisation flags such that I got something akin to this sort of explosion of combinations:

Now if you’re interested in that tool you can already find it on GitHub at https://github.com/cbtorture/tests and the results at https://github.com/cbtorture/findings (as you already have seen).

And your point is?

Okay, okay… I was getting to this. If we pivot to a completely different topic now then I can explain what the project I worked on last year (in 2022) was about.

Software verification

There are various worlds of programming, there are systems developers creating the underpinnings of what we use, applications developers that develop user software that runs on those systems and then there are those masochists that find pure joy in coming up with new and spectacular ways in which software of both the former two kinds can be tested.

There are a few ways software can be tested, from what I know (and I am not some industry expert so bare with my small knowledge):

- Manual testing

- Unit testing frameworks like JUnit

- Automated testing

- Fuzzing

- Symbolic execution

I want to focus on the second group, and specifically I will be referring to symbolic execution.

Symbolic execution

Symbolic execution of symex (sounds like an explosive, wait, that’s semtec) is a form of testing whereby one would want to test a whole body of code that has assertions scattered throughout. Some of these are not meant to be reached and would contain an assert(false) clause.

Now, in order to see if we can reach these different pieces of code which may be nested deeply in conditionals and so forth we must find a way to generate all paths of execution but in a smart way that can cull certain branches that would be impossible.

For example, take the below code:

int x;

if(x > 2)

{

if(x < 2)

{

assert(false);

}

else

{

...

}

}

Symbolic execution would start and split into two flows when it hits that first if(x>2) statement, one would be the path where x>2 is indeed true and another where it is false (or !(x>2) is true).

The way that symbolic execution works though is that the condition nested would not be considered, but rather only its else branch. This is due to the fact that we tacked on the initial condition and we had no state changes to the variable x, therefore we can immediately mark out the entirety of the if(x<2){} branch.

This has the added affect that we know no bug is present, as that false assertion (assert(false)) can never be reached under any circumstance.

This is a great technology as it is all symbolic and doesn’t require one to generate possible values but rather just build these large sort of conditional expressions and tack them together as you cross conditional cases and in certain circumstances invalidate entire sections of code as well.

Verifying C programs

Okay, so we know that software verification using symbolic execution can let one explore the entirety of a program’s flows in a way which tries to cull the search space if it knows they are impossible to reach.

But what is so special about this when it comes to C? Is this not something that is general enough to target any language? Well, yes it is general enough to target any language and a great example of a testing suite which has a symbolic execution mode is a tool known as JPF or Java Pathfinder which was infact worked on by Willem Viisser from my alma mata - Stellenbosch Universiteit!

However, we know that C has its funny sides to it, and we mentioned that earlier on. But one more tangent before we get to that - we need to talk about s e q u e n t i a l i z a t i o n techniques.

Lazy-CSeq

There is a tool known as Lazy-CSeq which performs various source-to-source translations on C programs. Basically meaning it has a so-called chainfile which looks something like this:

## Program simplification

workarounds

functiontracker

preinstrumenter

constants

spinlock

## Loop and control-flow transformation

switchtransformer

dowhileconverter

conditionextractor

## Program flattening

varnames

functionpointer

## Program flattening

## (function call handling, preinilining)

unroller

t_preinliner

## Program fattening

## (remaining inlining, etc.)

inliner

## Program flattening

## (Unrolling of transformation loops)

t_unroller

## Sequentialization

duplicator

condwaitconverter

lazyseq

## Instrumentation

instrumenter

## Analysis

mapper

feeder

cex

Now, you are probably thinking - what is all of this, why do I care and why. Slow down, I will tell you why. So, Lazy-CSeq reads in a C file pushes it into the first module listed in this chain, the module then parses it using PyCParser (a Python C parser), it then performs AST manipulations, which in effect change the code that will be output once the AST is flattened back into C code; hence the “source-to-source”.

This output is then fed into the next module and so on. When the end is reached then a symbolic execution engine like CMBC is launched and the testing begins. These transformations basically aid in augmenting/instrumenting the source code in certain ways to make the eventual testing more robust. This is where Tristan comes in.

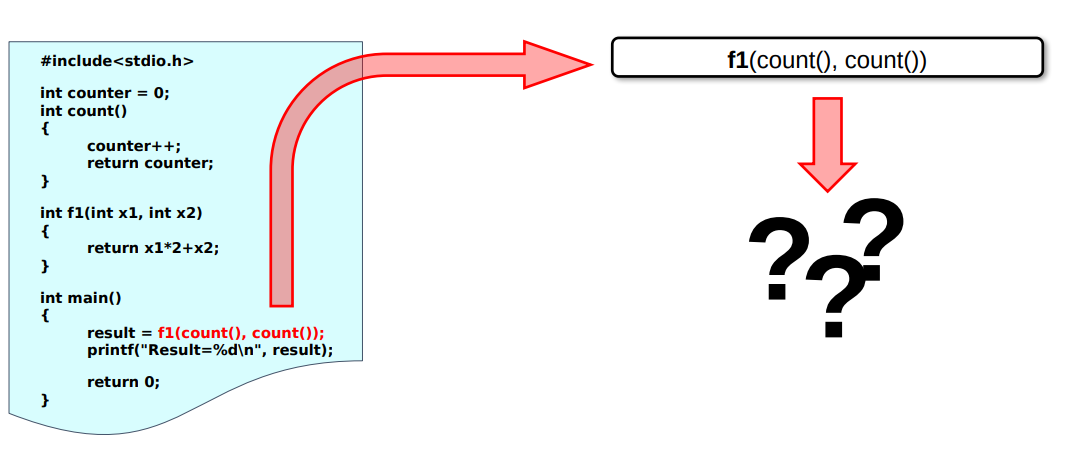

Introduction to pre-inlining

Before I started work on this project there was a module known as the preinliner. It does a pretty self-explanatory task of hoisting expressions passed to function calls out into variables. The reason for this is because the more verbose the better the simulation at the end would be.

SImulation? Well, this is because for multithreaded tests LazyCSeq would actually insert simulated context switches at the source code level such that it could simulate a real system as close as possible. Now it is quite the simulation because it is no where near as granular as this (which is pretty coarse) but the closer the better. You can therefore see that preinlining is a way to “get at” those spaces of execution in-between argument evaluation (in the case where those expressions themselves are function calls) and the final outer function call itself.

To be able to augment the source code to account for C’s behaviour as discussed earlier, I would need to modify this module (quite a lot) in order to get the effect.

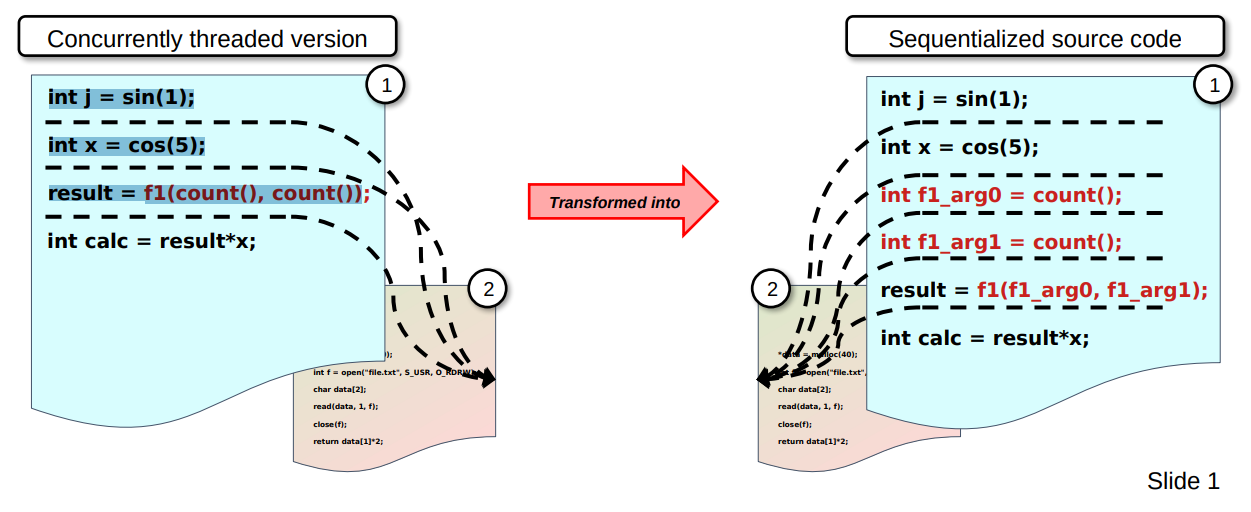

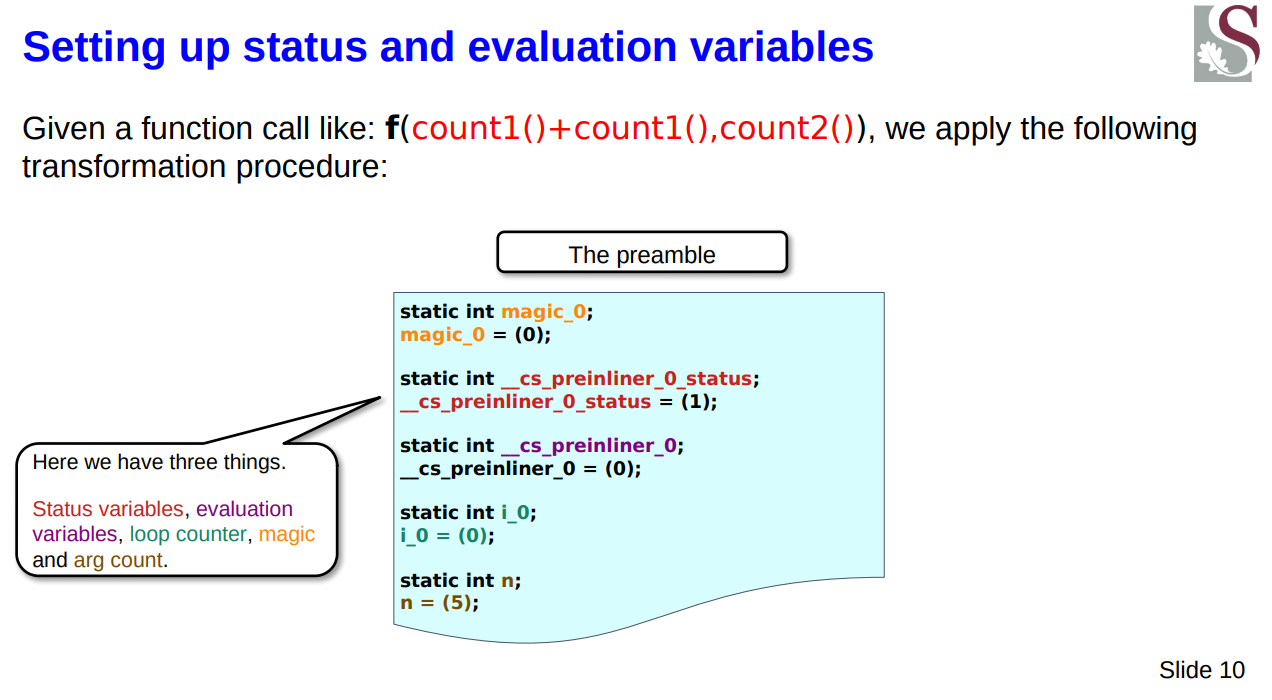

To show you an example from the slides to better illustrate it with actual code:

The left-hand side code is as follows:

int j = sin(1);

int x = cos(5);

result = f1(count(), count())

The right-hand side however is the following code:

int j = sin(1);

int x = cos(5);

int f1_arg0 = count();

int f1_arg1 = count();

result = f1(f1_arg0, f1_arg1);

As you can see we hoisted out the two calls to count() as the new variables f1_arg0 and f1_arg1, so that now we could insert fake context switches inbetween it like this:

# Switch here

int f1_arg0 = count();

# Switch here

int f1_arg1 = count();

# Switch here

result = f1(f1_arg0, f1_arg1);

# Switch here

That is a total of 4 places to switch, but comparing it to the non-preinlined version we would have:

# Switch here

result = f1(count(), count())

# Switch here

Which is only a mere two places to switch.

You can see how we can get a better simulation for the muli-threaded test cases in situations where nesting is more and more deeplily nested in terms of function calls.

We created a problem

This is great and all but now even if CBMC supported varying the function call order (which it doesn’t), we have now gained one thing by transforming it into a way more amenable to multi-threaded testing but at the same time there is a hard coding or ordering that has taken place. Even if CBMC gained functionality later it would not pick this up as we have hard coded the inner function calls now.

You can probably see where this is headed towards now and where the t_preinliner comes in.

Creating a new transformation

I needed to be able to re-work the existing AST transformations that could do a few things first of all.

Given a function call with some nested calls (further than just the first level of depth):

Beginnings

I needed to firstly generate all the preinline definitions by actually traversing downwards and discovering all of the function calls that were present. This wasn’t too difficult to do in practice as these were parsed into AST nodes and had runtime type information I could grasp at to see if it was a FuncCall object - that was easy enough.

The hard part was that I needed to generate what was effectively a set of dependencies such that I knew which sequence points were present. This means that I would be able to know which arguments could be evaluated out of order (in all orders) but which could only be considered for execution as well, as some function calls at level n would require nested calls at any level m > n to first be evaluated.

At the end I could collect these all into an in-memory data structure and then generate the correct source code transformation.

All orderings

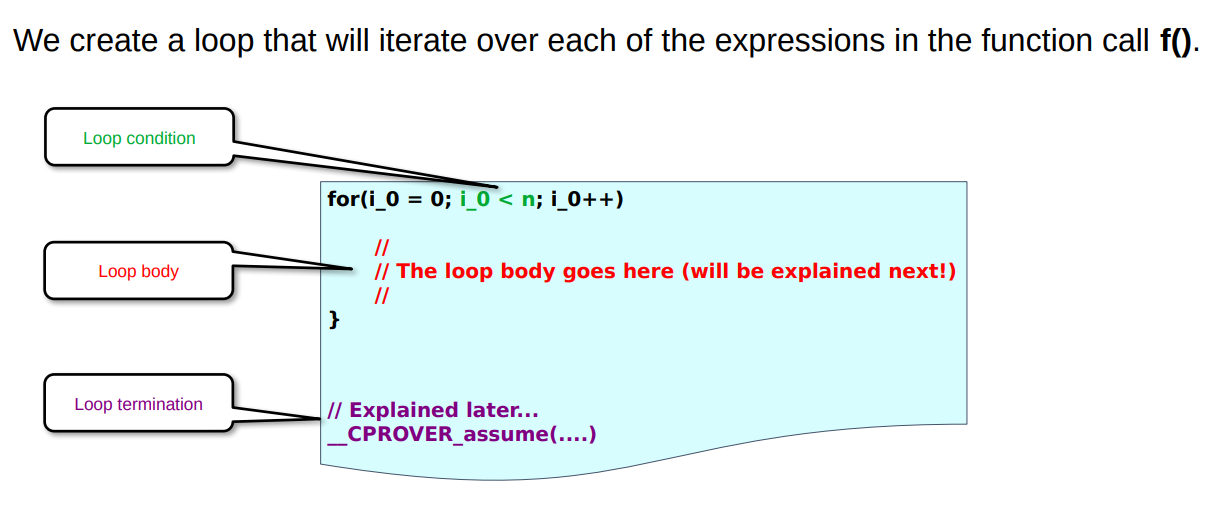

We construct a for loop which is finitely bound to the total number of arguments to function calls present at the statement-level function call.

This looks something like this:

for(i_0 = 0; i_0 < n; i_0++)

{

//

// The loop body goes here (will be explained next!)

//

}

The loop body

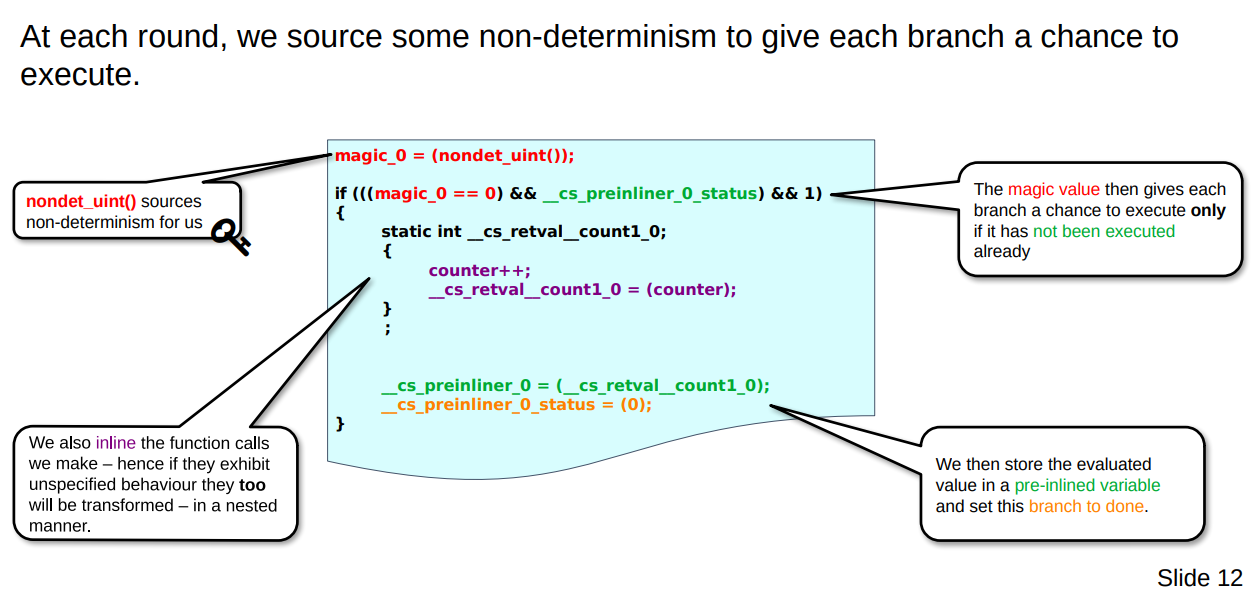

We now need to look at the body of the for loop as that is where the magic happens.

magic_0 = (nondet_uint());

At the beginning of each iteration we source a non-deterministic value using the nondet_int() method. By default CBMC will actually assign such a value to the variable but this is just to be more explicit. We will use this in order to give us variety in each iteration - you will see more about it soon.

if (((magic_0 == 0) && __cs_preinliner_0_status) && 1)

{

static int __cs_retval__count1_0;

{

counter++;

__cs_retval__count1_0 = (counter);

};

__cs_preinliner_0 = (__cs_retval__count1_0);

__cs_preinliner_0_status = (0);

}

What we see now, at the outermost level, is one of the many if statements we shall come across. Each one has a check for the value of the magic_0 value with a unique value to check against. This is used such that each iteration has a possibility of hitting one of these if-statements. The second condition that is checked is effectively a boolean in the form of __cs_preinliner_0_status. This is to prevent us from entering this if statement by random chance (due to magic_0 == 0 being true) if we have already entered it once before.

static int __cs_retval__count1_0;

{

counter++;

__cs_retval__count1_0 = (counter);

};

The block code contains the function to be evaluated but in its inlined form. As for us that count() function we saw earlier literally just did counter++ and then returned that. That return value is then placed here into __cs_retval__count1_0.

__cs_preinliner_0 = (__cs_retval__count1_0);

__cs_preinliner_0_status = (0);

When done executing the inlined-version of the function we then save its evaluated value into __cs_preinliner_0 and, as discussed earlier) make sure we don’t enter this evaluation code again by setting the status, __cs_preinliner_0_status, flag to false.

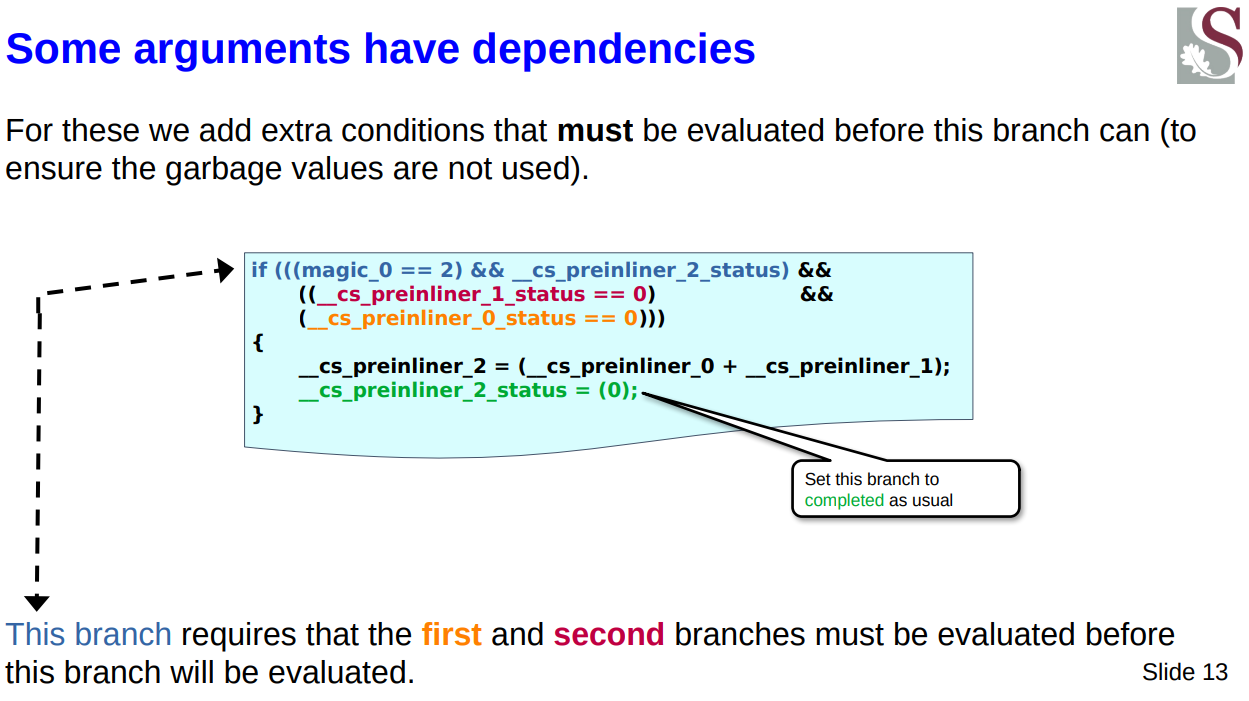

Handling dependencies

There are cases whereby we will need to execute certain combination-based expressions only if we have executed its children therein.

For example we have the expression count()+count(), this is inlined as follows:

__cs_preinliner_2 = (__cs_preinliner_0 + __cs_preinliner_1);

As we can see this requires that we evaluated whatever branch would store a value into __cs_preinliner_0 and whichever branch does the same for __cs_preinliner_1. Therefore in such a case this is what the generated if-statement looks like:

if (((magic_0 == 2) &&

__cs_preinliner_2_status) &&

((__cs_preinliner_1_status == 0) &&

(__cs_preinliner_0_status == 0)))

{

__cs_preinliner_2 = (__cs_preinliner_0 + __cs_preinliner_1);

__cs_preinliner_2_status = (0);

}

As you can see we use the status variables of the required dependencies to ensure they were executed by checking if they were set to false:

(__cs_preinliner_1_status == 0) && (__cs_preinliner_0_status == 0))

Bounding

There is most likely one question in your head now. We have a method of marking certain expressions as evaluating them such that we only evaluate them once. We also correctly handle dependencies.

But we have a finite number of iterations in the for-loop and this non-deterministic magic value which tries to give each evaluation a turn. But knowing such a thing doesn’t necessarily mean that each iteration will be a unique branch that gets executed, the same could in theory be hit (but just executed only once due to the status flag).

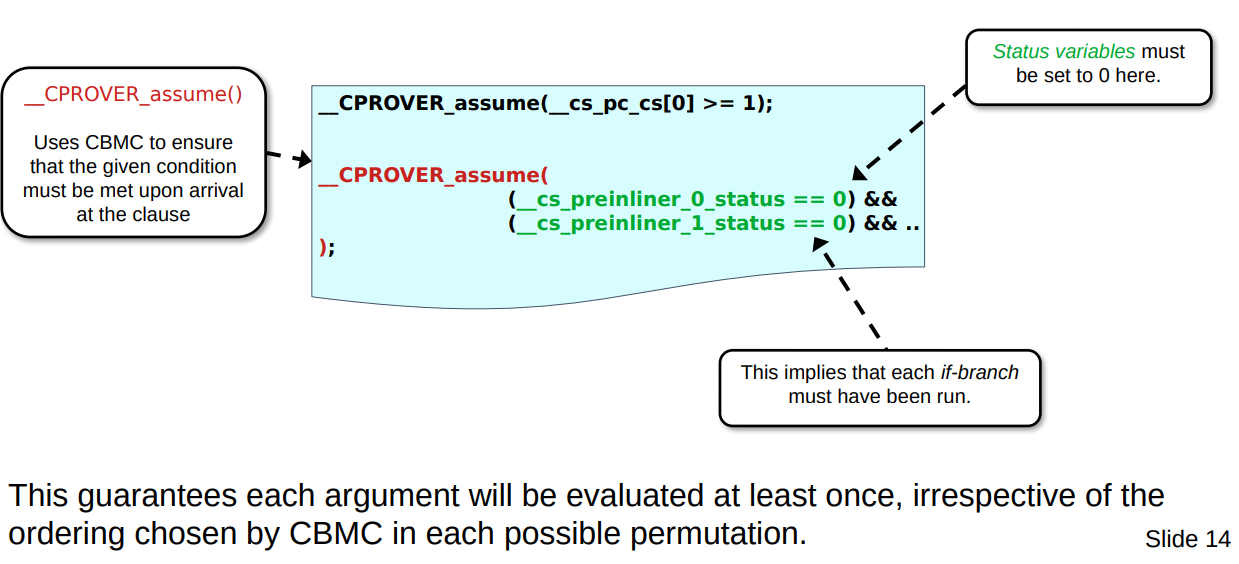

How do we tell CBMC that we want it to explore all the paths and ensure that each is visited as well? Well, this is where the handy __CPROVER_assume() comes in. It is placed after the for-loop such that when CBMC reads through the C source code it sees iut as a sort of boundary condition “that this condition must be true for every path of flow that made it possible to reach this statement”. This has the sort-of-inverse affect of affecting how code prior to it will be explored.

Therefore the assumption we do is:

__CPROVER_assume( (__cs_preinliner_0_status == 0) && (__cs_preinliner_1_status == 0) && .. );

This effectively tells CBMC that all of the status flags must have been set to false, implying all must have been explored. It will effectively rework the formulas such that we have a distinct magic value at each iteration given the constant boundary, therefore exploring all different ways the evaluation branches could be visited.

This means, at a higher level, exploring all different evaluations of the function call argument orderings.