What is a “CRXN”?

CRXN stands for Community Run eXperimental Network and it is exactly that. More specifically it’s an IPv4 and IPv6 IP-based computer network run by people all around the world (from Cape Town to Worcester to Russia to Germany) comprised of physical links and tunnel links (virtual links for layer 2 tunneling or layer 3 tunneling). The network is just a bunch of raspberry pis running some software in a certain configuration which I will get into in a moment.

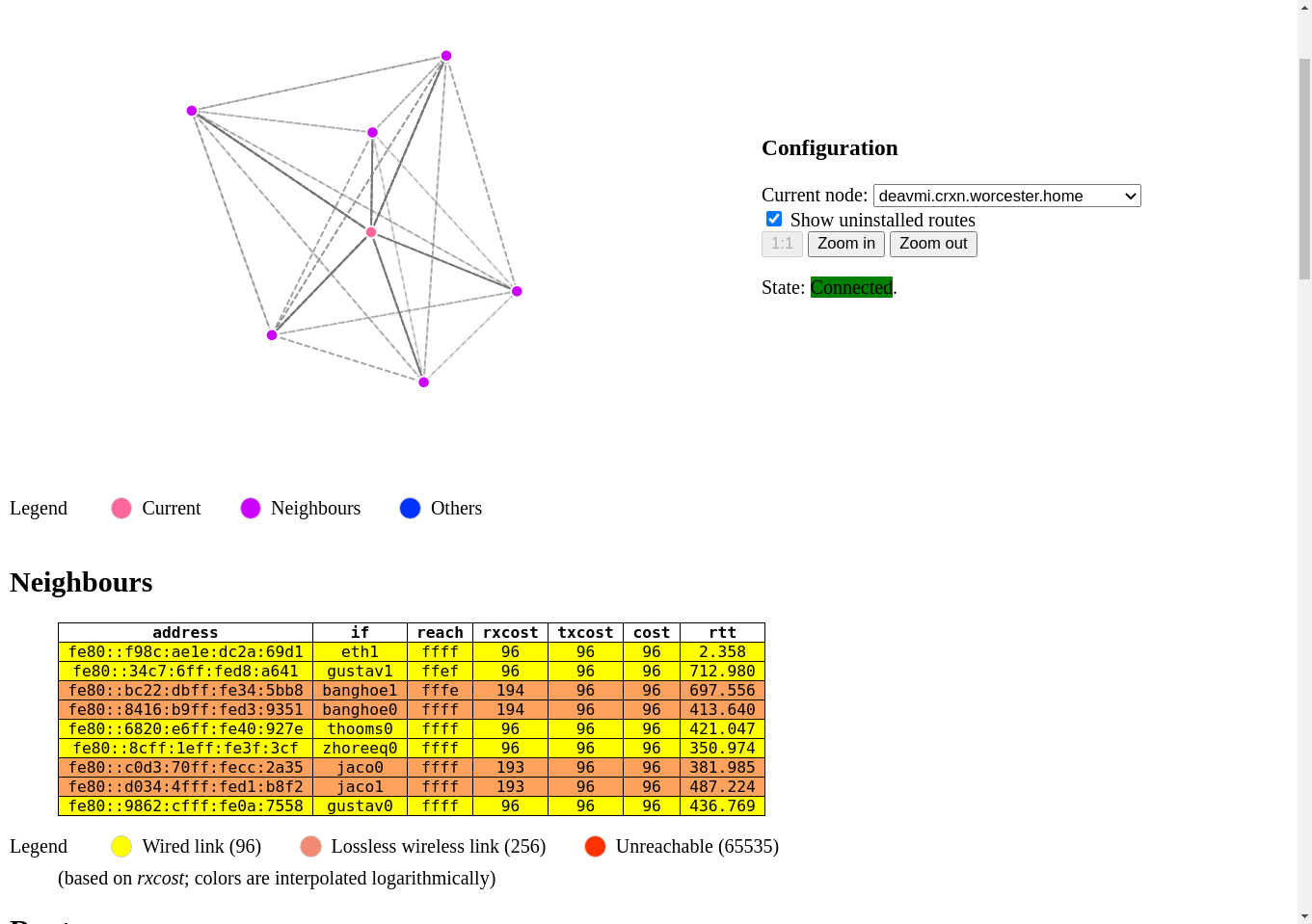

CRXN network map exported from the babel routing daemon's state

How it works

So CRXN is an internet (or inter-network) meaning that it is a group of computer networks interconnected to each other via links of different types. The type of links we have are 3 types to be correct. The first is a physical link and it looks something like this:

Ethernet switch with two routers linked to each other via it (routers not shown)

The image above is a simple Ethernet link between two routers (going via an EThernet switch). This is simple Linux networking really and as you would imagine you’d have an interface appear on both of them like as below:

Router 1 (by running ip addr):

3: eth1: <BROADCAST,MULTICAST,UP,LOWER_UP> mtu 1500 qdisc pfifo_fast state UP group default qlen 1000

link/ether 00:e0:4c:37:7b:25 brd ff:ff:ff:ff:ff:ff

inet 10.1.0.1/32 brd 10.1.0.1 scope global noprefixroute eth1

valid_lft forever preferred_lft forever

inet 169.254.206.25/16 brd 169.254.255.255 scope global noprefixroute eth1

valid_lft forever preferred_lft forever

inet6 fe80::d909:4141:2f5f:f942/64 scope link noprefixroute

valid_lft forever preferred_lft forever

Router 2 (by running ip addr):

3: eth1: <BROADCAST,MULTICAST,UP,LOWER_UP> mtu 1500 qdisc pfifo_fast state UP group default qlen 1000

link/ether f0:1e:34:12:2f:08 brd ff:ff:ff:ff:ff:ff

inet 169.254.31.162/16 brd 169.254.255.255 scope global noprefixroute eth1

valid_lft forever preferred_lft forever

inet 10.0.0.1/16 brd 10.0.255.255 scope global noprefixroute eth1

valid_lft forever preferred_lft forever

inet6 fd00:0:0:2::1/64 scope global noprefixroute

valid_lft forever preferred_lft forever

inet6 fe80::2d5b:4815:63cf:4173/64 scope link noprefixroute

valid_lft forever preferred_lft forever

Now obviously this isn’t the easiest method of peering with people other than myself as the distance for this cable is extremely short - in other words I cannot lay a cable from here to Kaapstadt (Cape Town). So then how do we accomplish a link to those nodes as remote as Cape Town, Germany and even Russia? Well we use tunnels of course!

Setting up tunnels

The beginnings: Yggdrasil’s tunnel routing

Setting up tunnels is genereally an easy process, well depending on what software you use, but in the case of the tooling I have used in the past throughout the development of CRXN it actually started off somewhat non-trivial and then got extremely easy.

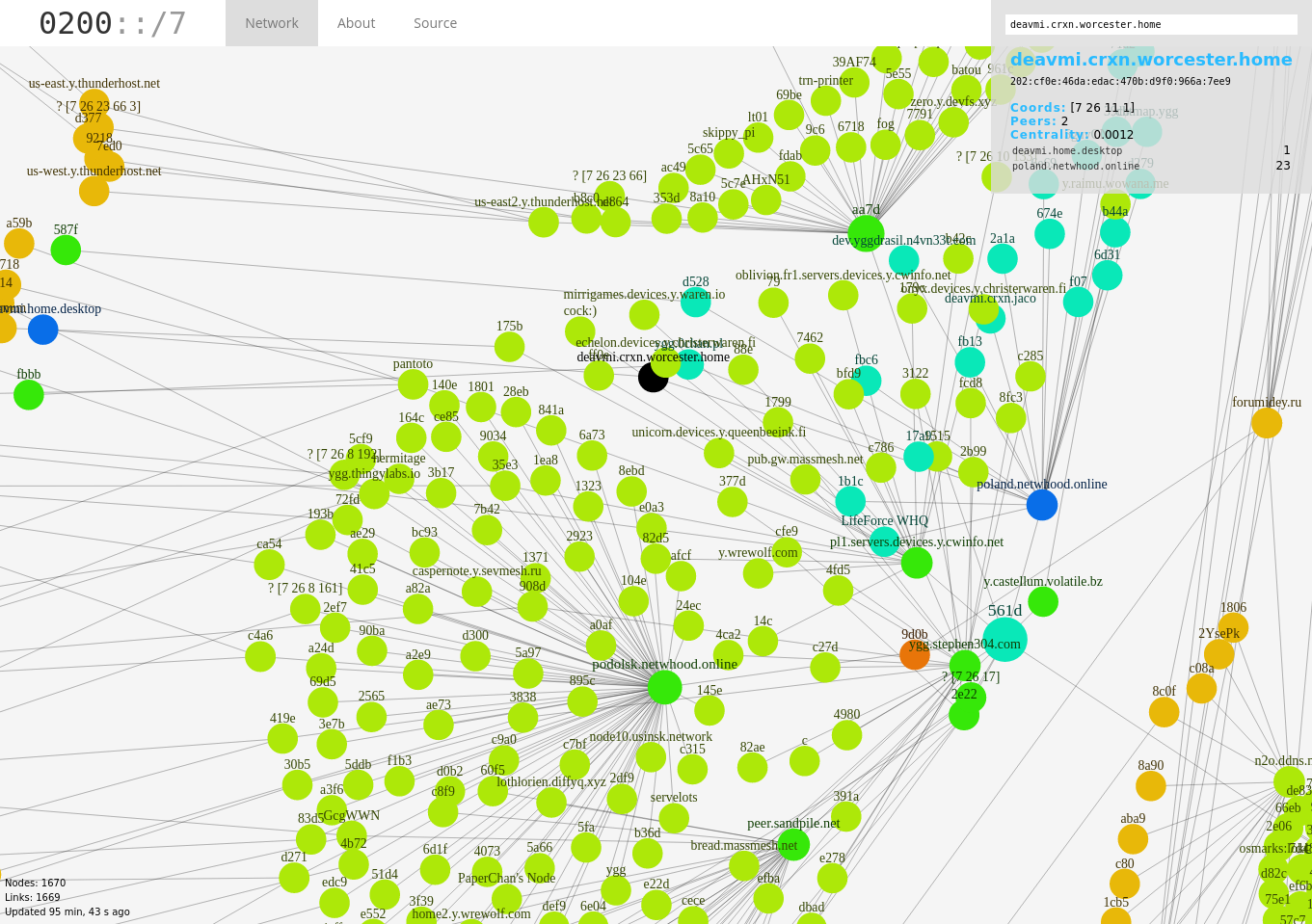

The first method we used was to use tunnel routing that was built into the overlay network we use (now not exclusively) for tunneling data over - Yggdrasil! Yggdrasil is an overlay network that uses a spanning tree and DHT (among other protocols that I don’t understand) for routing data between nodes indicated via their public key. So what this gives you at the end of the day is a way to get data from node A to node B with their respective public keys.

A map of Yggdrasil's spanning tree network (the overlay network we used for tunneling)

One application of this is to use this new transport to move IP packets to and fro node A and node B - this is what Yggdrasil CKR does! We setup the subnets we want to allow the Yggdrasil daemon to tunnel source wise (such that any IP packets with source IPs not matching when they go into the tun interface are dropped by the driver - (a.k.a. Yggdrasil)). Then we specify which destination subnets should be allowed to tunnel (once the source checks check out) and to whom (which node) they should be delivered to. The nodes on the other ends, let’s say node B, will then have certain IPs mapped to it at node A and anything that the user on node A puts into the tun interface that matches those will pop out of the tun interface at node B’s side (also assuming it has destination routes for that node (which prevents you tunneling to anyone I guess).

So what we ended up doing was then, once the Yggdrasil side of things were configured, adding routes to those subnets to go to the local network and via the tun device such that any matching packets get swallowed by the kernel and then handed to the tun driver which in part works with the userspace Yggdrasil driver (hand in hand) to get the packet to pop out of the remote node’s tun interface at the other end of this virtual pipe we have constructed that pipes over this spanning tree as shown above (and all for free! - this being a major reason of why I chose this method and also because it was simple, no OpenVPN or something like that (not that I have ever tried to set that up before but I feel like it it WAAY more complicated than this).

This was right in the beginning when we used only tunnel routing so this simple IP tunnel worked out well but it had some shortcomings (which I will talk about in the next section) that would affect me later when I wanted to deploy a dynamic routing daemon.

Make tunneling GREat again: How GRE solved issues regarding Babel and multicast

The time for static routing came to a close when I decided that this static shit wasn’t sustainable at all. Manages adding routes and all was just gonna get expensive and managing redundant links (and no link testing for when a router is down and therefore route) meant the network wouldn’t be able to scale. So then why not just run babel over the tun interface that yggdrasil would run? That would be possible theoretically but in practice this (Yggdrasil’s tun handler) wasn’t a completely compliant driver in the sense that multicast wasn’t supported (which is needed by babel for neighbor discovery).

SO what I would do then is get the GRE (Generic Routing Encapsulation) tunneling protocol to run over CJDNS or Yggdrasil but because I was using GRE version 4 I wasn’t able to natively use GRE over the IPv6 link (that the tun interface of Yggdrasil/CJDNS provided) for peering therefore I needed a link that could carry IPv4 - how did I do that? Well I basically combined the first technique with tunneling routing supported Yggdrasil/CJDNS such that the GRE traffic could move between routers/nodes. So I would have an IP link created via Yggdrasil or CJDNS’s tunnel routing between 192.168.99.1 and 192.168.99.2 and a route (host route added for both and address assigned for packet acceptance) and then I would have a link that I could run GRE v4 over )over this IPv4 link). GRE would provide me an interface that I named babel0 on both nodes, I would then add an interface declaration to babel’s configuration file (indicating it should listen for advertisements on this link and send out its own too) and after this I would be at the point whereby Babel was working and doing its routing magic (building and maintaining the routing table).

My fall from grace in userspace: fastd (it’s slower though)

So despite its name, fastd will be evoked on a context switch from kernel mode (for the tap driver) to userspace for the handler (fastd) which means register saves and transitions and loading new register sets from memory) or in other words something very slow. Compare this to GRETAP or VXLAN which are in kernel mode - they will stay there (no switch needed) hence faster. However, I’m all about that Minix/Andew Tanenbaum life so I like running everything in userspace - hell the network stack should even be entirely in userspace (the kernel shouldn’t even know what a network “is”) but that is a topic for another discussion. Anyways, the reason I chose fastd is firstly because it is a layer 2 VPN providing a tap device with Ethernet support and secondly (what separates it from the former two solutions mentioned) it is easy to configure (okay I have never tried the other two but anything that uses ip tunnel or is like normal GRE is aids - I wanted a daemon that would run by itself - not some weird hidden thing chilling in the kernel) - in either case a more honest version is that regardless of a comparison, fastd is just very simple to configure. Basically just keys (for encryption), interface selection and then the peer you want to connect/tunnel to and a handy little post-interface-up script that it runs on tunnel-up state which you can use to configure an IP for the interface which Babel would need (same for my previous solution of GRE) and then also add a route (with a protocol) that babel must redistribute for your subnet.

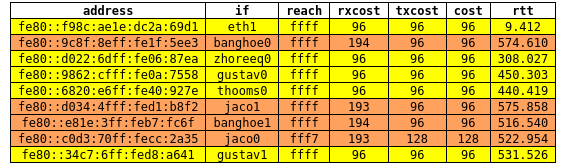

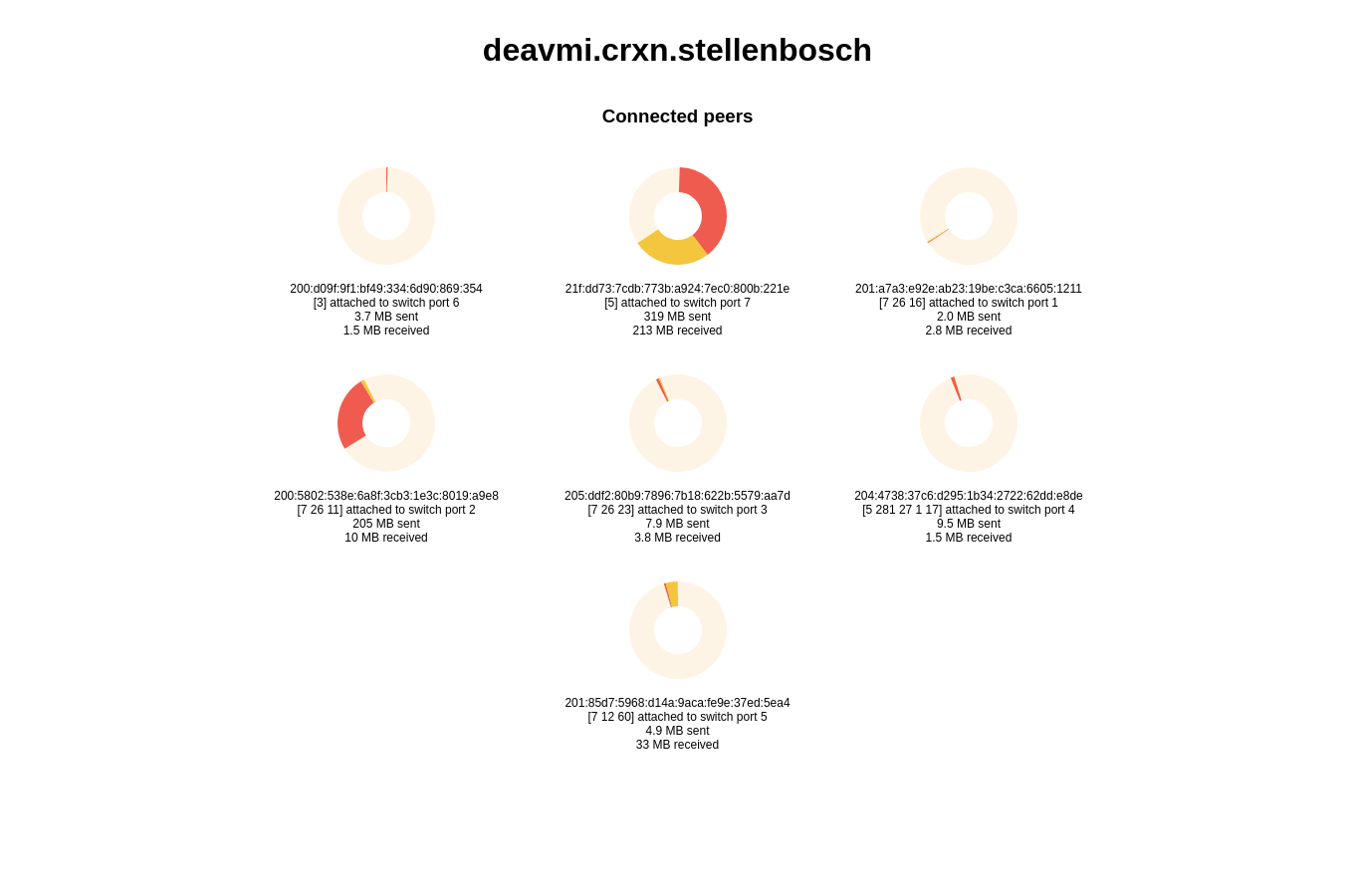

Babel neighbors tunneled over fastd (everything but eth1)

And that’s where we are now with regards to routing - babel makes it really easy and I never have to worry about network maintenance (except for proper subnet management but the list of routes kind of makes that obvious - a.k.a. which ones are in use and which ones are not - or in other words available for allocation).

Where we are now?

Currently we have about 7-ish nodes I think. I run 4 (one of them I meant to be at Stellenbosch with me but my university is cucked), Gustav Meyer (OGustav) runs 1, zhoreeq runs 1, acetone (peered via zhoreeq) runs 1, thooms runs 1 node (in a closet with a custom case with two computers tied into it) damn we should have a blog post about the whacky places people are running their routers in - there are a few!) and then there are other people peered like skippy and chris but using outdated static routing so they need to upgrade rather soon (their connections still work but it isn’t optimal) as it still means there is some manual routing having to be done. Randyr will be peering very soon too! Caskd will be peering a little later this year or next year (yikes). And who knows - maybe even more will - the nice thing is they don’t need the go ahead from me, they just peer and babel sorts it out!

We have a map which is up most of the time at http://deavmi.assigned.network:4444. We also have a nice tutorial on peering that is almost complete here.

Cool, an internet but why?

Because I can and it’s super fun. I mean how often do you as a lame IPv4 user (coombrain) ever get to run a service and just have it readily available for access without port forwarding which cuts some protocols out from working - never (unless you got a public subnet allocated to you which I doubt). So we run whatever we would want to run on this network knowing that as soon as a process binds and starts listening on a given address and port that anyone can access it from that address and port. No additional setup as it should be.

There a lot of things I am running. Let’s take a look at some of them:

zhoreeq's running a 4chan-like imageboard available at 10.6.2.1/bruh (and a crxn-dedicated one at 10.6.2.1/crxn

I, deavmi, run a SFU server which can be used for video calling. It uses any available connection hence it may not actually connec (the video feed) over CRXN if other connections are available and chosen first. Available at 10.0.0.2:8443

Monitorix monitoring the system statistics of gustav's router (10.6.4.1)

Yggdrasil statistics server running on deavmi's machine at 10.6.3.1

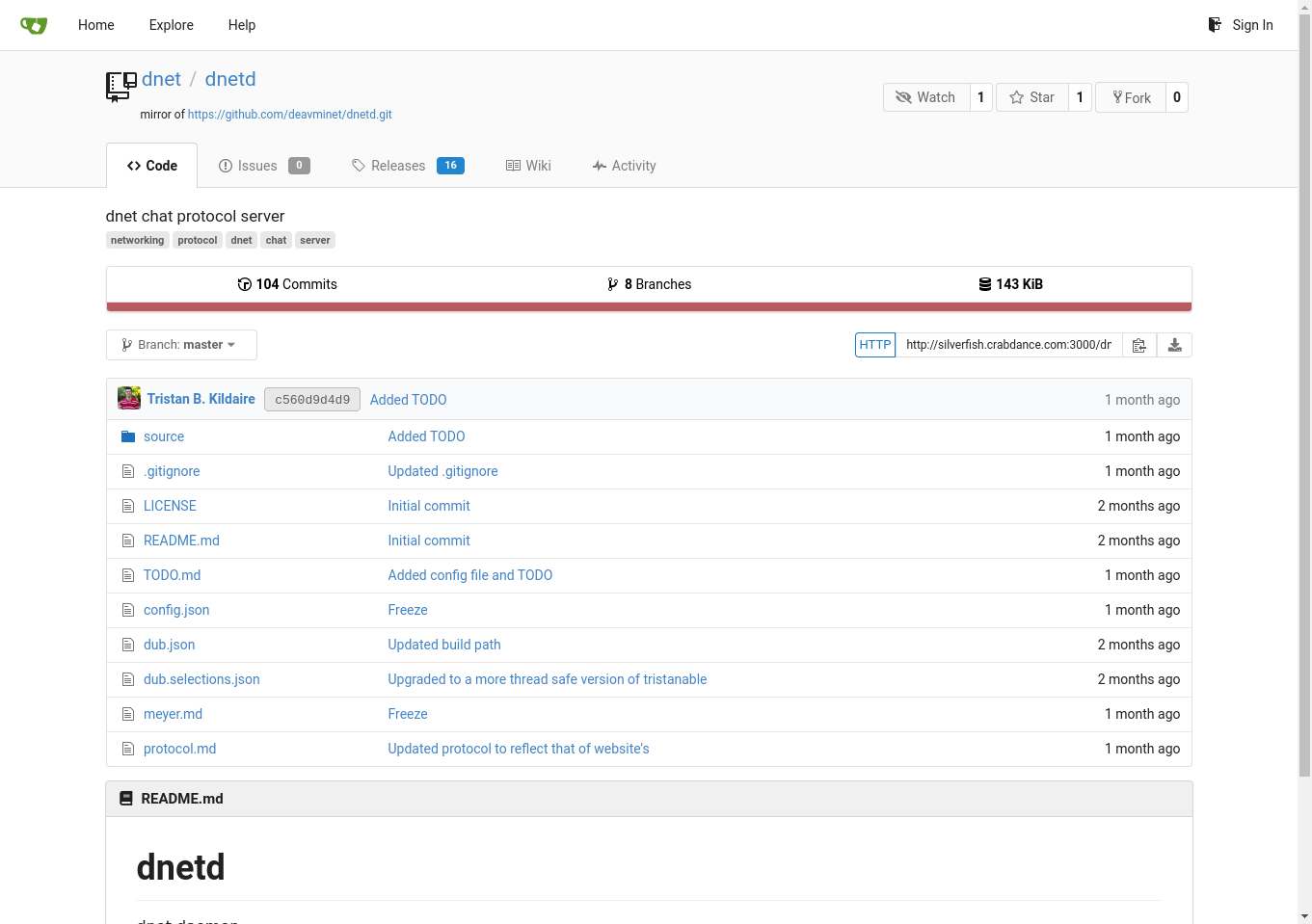

A Gitea server running which hosts deavmi's projects (mirroring from GitHub) at 10.0.0.8

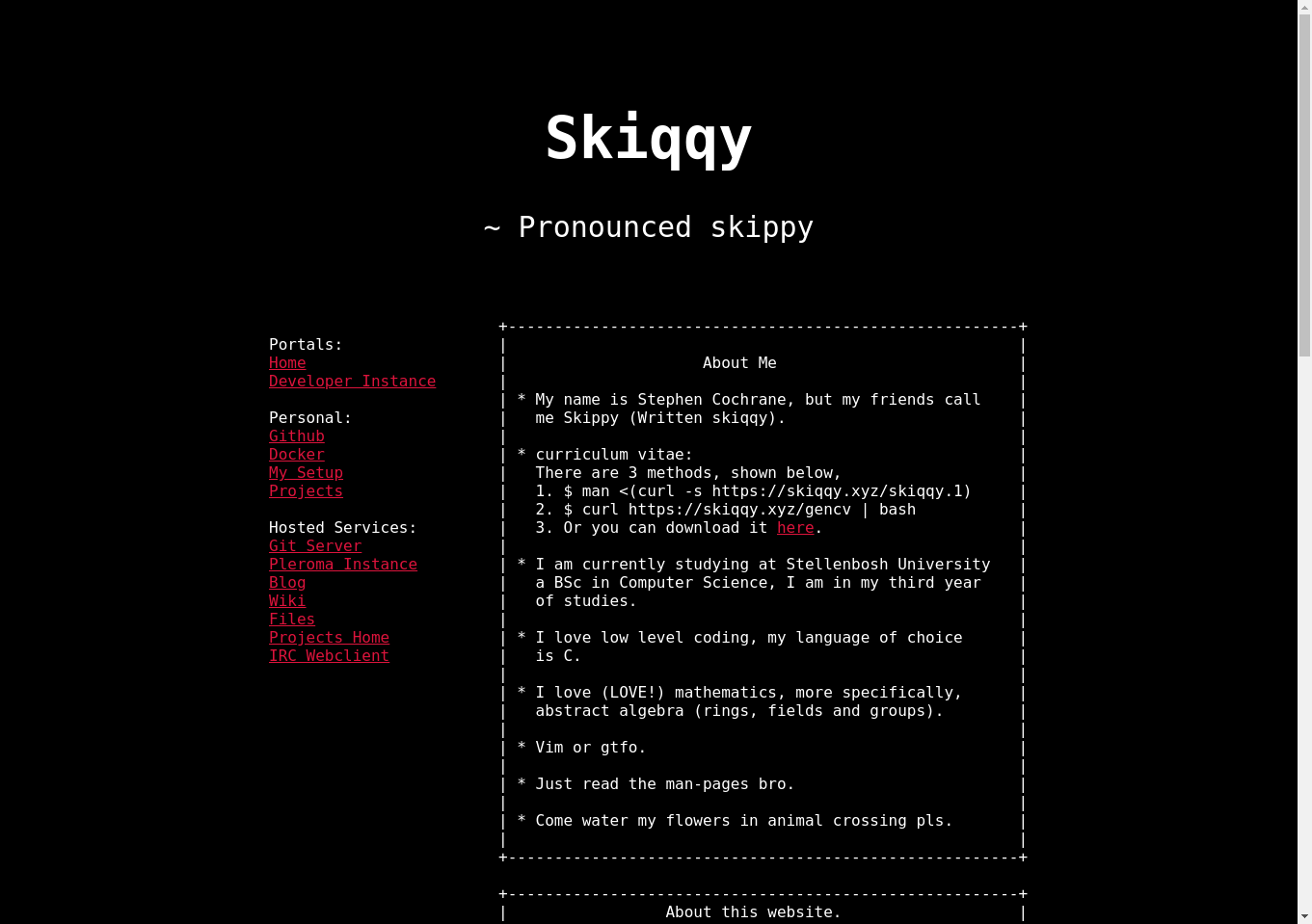

This dude, skiqqy's, website at 10.6.6.1